Analyzing Data from Multiple Files

Last updated on 2023-09-19 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How can I do the same operations on many different files?

Objectives

- Use a library function to get a list of filenames that match a wildcard pattern.

- Write a

forloop to process multiple files.

As a final piece to processing our inflammation data, we need a way

to get a list of all the files in our data directory whose

names start with inflammation- and end with

.csv. The following library will help us to achieve

this:

PYTHON

import globThe glob library contains a function, also called

glob, that finds files and directories whose names match a

pattern. We provide those patterns as strings: the character

* matches zero or more characters, while ?

matches any one character. We can use this to get the names of all the

CSV files in the current directory:

PYTHON

print(glob.glob('inflammation*.csv'))OUTPUT

['inflammation-05.csv', 'inflammation-11.csv', 'inflammation-12.csv', 'inflammation-08.csv',

'inflammation-03.csv', 'inflammation-06.csv', 'inflammation-09.csv', 'inflammation-07.csv',

'inflammation-10.csv', 'inflammation-02.csv', 'inflammation-04.csv', 'inflammation-01.csv']As these examples show, glob.glob’s result is a list of

file and directory paths in arbitrary order. This means we can loop over

it to do something with each filename in turn. In our case, the

“something” we want to do is generate a set of plots for each file in

our inflammation dataset.

If we want to start by analyzing just the first three files in

alphabetical order, we can use the sorted built-in function

to generate a new sorted list from the glob.glob

output:

PYTHON

import glob

import numpy

import matplotlib.pyplot

filenames = sorted(glob.glob('inflammation*.csv'))

filenames = filenames[0:3]

for filename in filenames:

print(filename)

data = numpy.loadtxt(fname=filename, delimiter=',')

fig = matplotlib.pyplot.figure(figsize=(10.0, 3.0))

axes1 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 1)

axes2 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 2)

axes3 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 3)

axes1.set_ylabel('average')

axes1.plot(numpy.mean(data, axis=0))

axes2.set_ylabel('max')

axes2.plot(numpy.amax(data, axis=0))

axes3.set_ylabel('min')

axes3.plot(numpy.amin(data, axis=0))

fig.tight_layout()

matplotlib.pyplot.show()OUTPUT

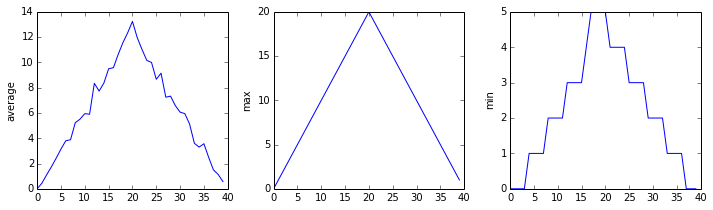

inflammation-01.csv

OUTPUT

inflammation-02.csv

OUTPUT

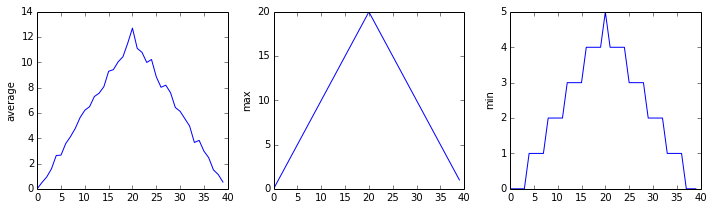

inflammation-03.csv

The plots generated for the second clinical trial file look very similar to the plots for the first file: their average plots show similar “noisy” rises and falls; their maxima plots show exactly the same linear rise and fall; and their minima plots show similar staircase structures.

The third dataset shows much noisier average and maxima plots that are far less suspicious than the first two datasets, however the minima plot shows that the third dataset minima is consistently zero across every day of the trial. If we produce a heat map for the third data file we see the following:

We can see that there are zero values sporadically distributed across all patients and days of the clinical trial, suggesting that there were potential issues with data collection throughout the trial. In addition, we can see that the last patient in the study didn’t have any inflammation flare-ups at all throughout the trial, suggesting that they may not even suffer from arthritis!

PYTHON

import glob

import numpy

import matplotlib.pyplot

filenames = sorted(glob.glob('inflammation*.csv'))

data0 = numpy.loadtxt(fname=filenames[0], delimiter=',')

data1 = numpy.loadtxt(fname=filenames[1], delimiter=',')

fig = matplotlib.pyplot.figure(figsize=(10.0, 3.0))

matplotlib.pyplot.ylabel('Difference in average')

matplotlib.pyplot.plot(numpy.mean(data0, axis=0) - numpy.mean(data1, axis=0))

fig.tight_layout()

matplotlib.pyplot.show()Generate Composite Statistics

Use each of the files once to generate a dataset containing values averaged over all patients by completing the code inside the loop given below:

PYTHON

filenames = glob.glob('inflammation*.csv')

composite_data = numpy.zeros((60,40))

for filename in filenames:

# sum each new file's data into composite_data as it's read

#

# and then divide the composite_data by number of samples

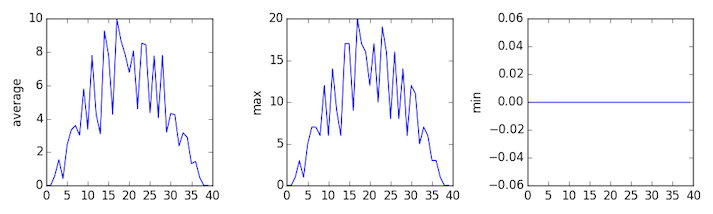

composite_data = composite_data / len(filenames)Then use pyplot to generate average, max, and min for all patients.

PYTHON

import glob

import numpy

import matplotlib.pyplot

filenames = glob.glob('inflammation*.csv')

composite_data = numpy.zeros((60,40))

for filename in filenames:

data = numpy.loadtxt(fname = filename, delimiter=',')

composite_data = composite_data + data

composite_data = composite_data / len(filenames)

fig = matplotlib.pyplot.figure(figsize=(10.0, 3.0))

axes1 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 1)

axes2 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 2)

axes3 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 3)

axes1.set_ylabel('average')

axes1.plot(numpy.mean(composite_data, axis=0))

axes2.set_ylabel('max')

axes2.plot(numpy.amax(composite_data, axis=0))

axes3.set_ylabel('min')

axes3.plot(numpy.amin(composite_data, axis=0))

fig.tight_layout()

matplotlib.pyplot.show()After spending some time investigating the heat map and statistical plots, as well as doing the above exercises to plot differences between datasets and to generate composite patient statistics, we gain some insight into the twelve clinical trial datasets.

The datasets appear to fall into two categories:

- seemingly “ideal” datasets that agree excellently with

Dr. Maverick’s claims, but display suspicious maxima and minima (such as

inflammation-01.csvandinflammation-02.csv) - “noisy” datasets that somewhat agree with Dr. Maverick’s claims, but show concerning data collection issues such as sporadic missing values and even an unsuitable candidate making it into the clinical trial.

In fact, it appears that all three of the “noisy” datasets

(inflammation-03.csv, inflammation-08.csv, and

inflammation-11.csv) are identical down to the last value.

Armed with this information, we confront Dr. Maverick about the

suspicious data and duplicated files.

Dr. Maverick has admitted to fabricating the clinical data for their drug trial. They did this after discovering that the initial trial had several issues, including unreliable data recording and poor participant selection. In order to prove the efficacy of their drug, they created fake data. When asked for additional data, they attempted to generate more fake datasets, and also included the original poor-quality dataset several times in order to make the trials seem more realistic.

Congratulations! We’ve investigated the inflammation data and proven that the datasets have been synthetically generated.

But it would be a shame to throw away the synthetic datasets that have taught us so much already, so we’ll forgive the imaginary Dr. Maverick and continue to use the data to learn how to program.