Repeating Actions with Loops

Last updated on 2023-09-19 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How can I do the same operations on many different values?

Objectives

- Explain what a

forloop does. - Correctly write

forloops to repeat simple calculations. - Trace changes to a loop variable as the loop runs.

- Trace changes to other variables as they are updated by a

forloop.

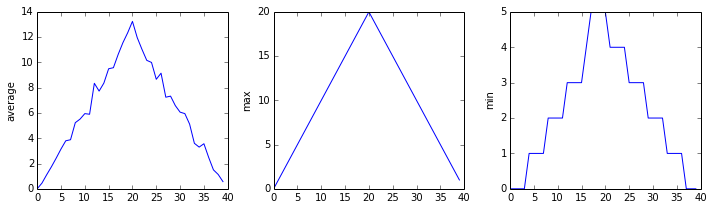

In the episode about visualizing data, we wrote Python code that

plots values of interest from our first inflammation dataset

(inflammation-01.csv), which revealed some suspicious

features in it.

We have a dozen data sets right now and potentially more on the way if Dr. Maverick can keep up their surprisingly fast clinical trial rate. We want to create plots for all of our data sets with a single statement. To do that, we’ll have to teach the computer how to repeat things.

An example task that we might want to repeat is accessing numbers in a list, which we will do by printing each number on a line of its own.

PYTHON

odds = [1, 3, 5, 7]In Python, a list is basically an ordered collection of elements, and

every element has a unique number associated with it — its index. This

means that we can access elements in a list using their indices. For

example, we can get the first number in the list odds, by

using odds[0]. One way to print each number is to use four

print statements:

PYTHON

print(odds[0])

print(odds[1])

print(odds[2])

print(odds[3])OUTPUT

1

3

5

7This is a bad approach for three reasons:

Not scalable. Imagine you need to print a list that has hundreds of elements. It might be easier to type them in manually.

Difficult to maintain. If we want to decorate each printed element with an asterisk or any other character, we would have to change four lines of code. While this might not be a problem for small lists, it would definitely be a problem for longer ones.

Fragile. If we use it with a list that has more elements than what we initially envisioned, it will only display part of the list’s elements. A shorter list, on the other hand, will cause an error because it will be trying to display elements of the list that do not exist.

PYTHON

odds = [1, 3, 5]

print(odds[0])

print(odds[1])

print(odds[2])

print(odds[3])OUTPUT

1

3

5ERROR

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

IndexError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-3-7974b6cdaf14> in <module>()

3 print(odds[1])

4 print(odds[2])

----> 5 print(odds[3])

IndexError: list index out of rangeHere’s a better approach: a for loop

PYTHON

odds = [1, 3, 5, 7]

for num in odds:

print(num)OUTPUT

1

3

5

7This is shorter — certainly shorter than something that prints every number in a hundred-number list — and more robust as well:

PYTHON

odds = [1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11]

for num in odds:

print(num)OUTPUT

1

3

5

7

9

11The improved version uses a for loop to repeat an operation — in this case, printing — once for each thing in a sequence. The general form of a loop is:

PYTHON

for variable in collection:

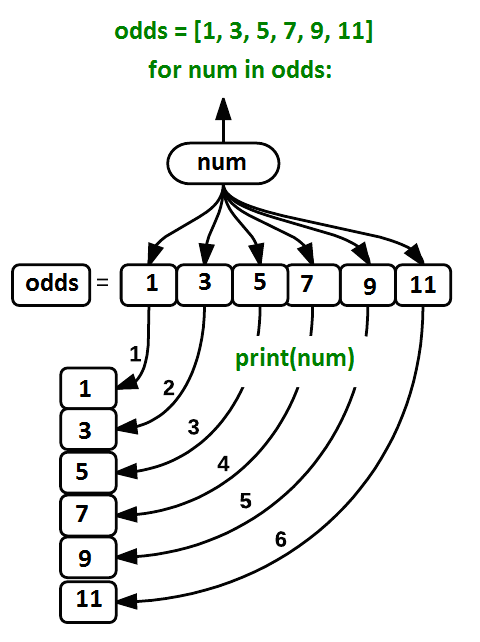

# do things using variable, such as printUsing the odds example above, the loop might look like this:

where each number (num) in the variable

odds is looped through and printed one number after

another. The other numbers in the diagram denote which loop cycle the

number was printed in (1 being the first loop cycle, and 6 being the

final loop cycle).

We can call the loop

variable anything we like, but there must be a colon at the end of

the line starting the loop, and we must indent anything we want to run

inside the loop. Unlike many other languages, there is no command to

signify the end of the loop body (e.g. end for); everything

indented after the for statement belongs to the loop.

What’s in a name?

In the example above, the loop variable was given the name

num as a mnemonic; it is short for ‘number’. We can choose

any name we want for variables. We might just as easily have chosen the

name banana for the loop variable, as long as we use the

same name when we invoke the variable inside the loop:

PYTHON

odds = [1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11]

for banana in odds:

print(banana)OUTPUT

1

3

5

7

9

11It is a good idea to choose variable names that are meaningful, otherwise it would be more difficult to understand what the loop is doing.

Here’s another loop that repeatedly updates a variable:

PYTHON

length = 0

names = ['Curie', 'Darwin', 'Turing']

for value in names:

length = length + 1

print('There are', length, 'names in the list.')OUTPUT

There are 3 names in the list.It’s worth tracing the execution of this little program step by step.

Since there are three names in names, the statement on line

4 will be executed three times. The first time around,

length is zero (the value assigned to it on line 1) and

value is Curie. The statement adds 1 to the

old value of length, producing 1, and updates

length to refer to that new value. The next time around,

value is Darwin and length is 1,

so length is updated to be 2. After one more update,

length is 3; since there is nothing left in

names for Python to process, the loop finishes and the

print function on line 5 tells us our final answer.

Note that a loop variable is a variable that is being used to record progress in a loop. It still exists after the loop is over, and we can re-use variables previously defined as loop variables as well:

PYTHON

name = 'Rosalind'

for name in ['Curie', 'Darwin', 'Turing']:

print(name)

print('after the loop, name is', name)OUTPUT

Curie

Darwin

Turing

after the loop, name is TuringNote also that finding the length of an object is such a common

operation that Python actually has a built-in function to do it called

len:

PYTHON

print(len([0, 1, 2, 3]))OUTPUT

4len is much faster than any function we could write

ourselves, and much easier to read than a two-line loop; it will also

give us the length of many other things that we haven’t met yet, so we

should always use it when we can.

From 1 to N

Python has a built-in function called range that

generates a sequence of numbers. range can accept 1, 2, or

3 parameters.

- If one parameter is given,

rangegenerates a sequence of that length, starting at zero and incrementing by 1. For example,range(3)produces the numbers0, 1, 2. - If two parameters are given,

rangestarts at the first and ends just before the second, incrementing by one. For example,range(2, 5)produces2, 3, 4. - If

rangeis given 3 parameters, it starts at the first one, ends just before the second one, and increments by the third one. For example,range(3, 10, 2)produces3, 5, 7, 9.

Using range, write a loop that prints the first 3

natural numbers:

PYTHON

1

2

3PYTHON

for number in range(1, 4):

print(number)The body of the loop is executed 6 times.

PYTHON

result = 1

for number in range(0, 3):

result = result * 5

print(result)PYTHON

numbers = [124, 402, 36]

summed = 0

for num in numbers:

summed = summed + num

print(summed)Computing the Value of a Polynomial

The built-in function enumerate takes a sequence (e.g. a

list) and generates a new sequence of the

same length. Each element of the new sequence is a pair composed of the

index (0, 1, 2,…) and the value from the original sequence:

PYTHON

for idx, val in enumerate(a_list):

# Do something using idx and valThe code above loops through a_list, assigning the index

to idx and the value to val.

Suppose you have encoded a polynomial as a list of coefficients in the following way: the first element is the constant term, the second element is the coefficient of the linear term, the third is the coefficient of the quadratic term, etc.

PYTHON

x = 5

coefs = [2, 4, 3]

y = coefs[0] * x**0 + coefs[1] * x**1 + coefs[2] * x**2

print(y)OUTPUT

97Write a loop using enumerate(coefs) which computes the

value y of any polynomial, given x and

coefs.

PYTHON

y = 0

for idx, coef in enumerate(coefs):

y = y + coef * x**idx